While the engine serves as the heart of a vehicle, the transmission acts as its central nervous system, translating raw combustion energy into controlled, purposeful movement. An engine operating without a transmission would be practically useless, as it lacks the mechanical leverage to move a heavy vehicle from a standstill or the gear range to sustain highway speeds without self-destructing. The transmission bridges the gap between the high-speed rotation of the engine and the varied torque requirements of the road. This technical overview will provide a clear understanding of what a transmission is, the mechanical principles of gear ratios, and the distinct engineering differences between manual, automatic, and CVT systems. By the end of this guide, you will grasp why this component is the most critical link in the modern drivetrain.

The Fundamental Mechanics and Purpose of an Automotive Transmission

At its core, a transmission is a power-matching device. To understand its importance, one must first grasp the concept of the “Power Band.” Internal combustion engines are specialized machines that only produce peak torque and horsepower within a relatively narrow range of revolutions per minute (RPM). Most modern engines idle between 600-800 RPM and reach their mechanical limits—the redline—near 6,000 or 7,000 RPM. Without a transmission, a car would be forced to use a single gear ratio. This would result in a vehicle that either accelerates quickly but cannot exceed 20 mph, or a vehicle that can do 100 mph but lacks the torque to move from a stationary position.

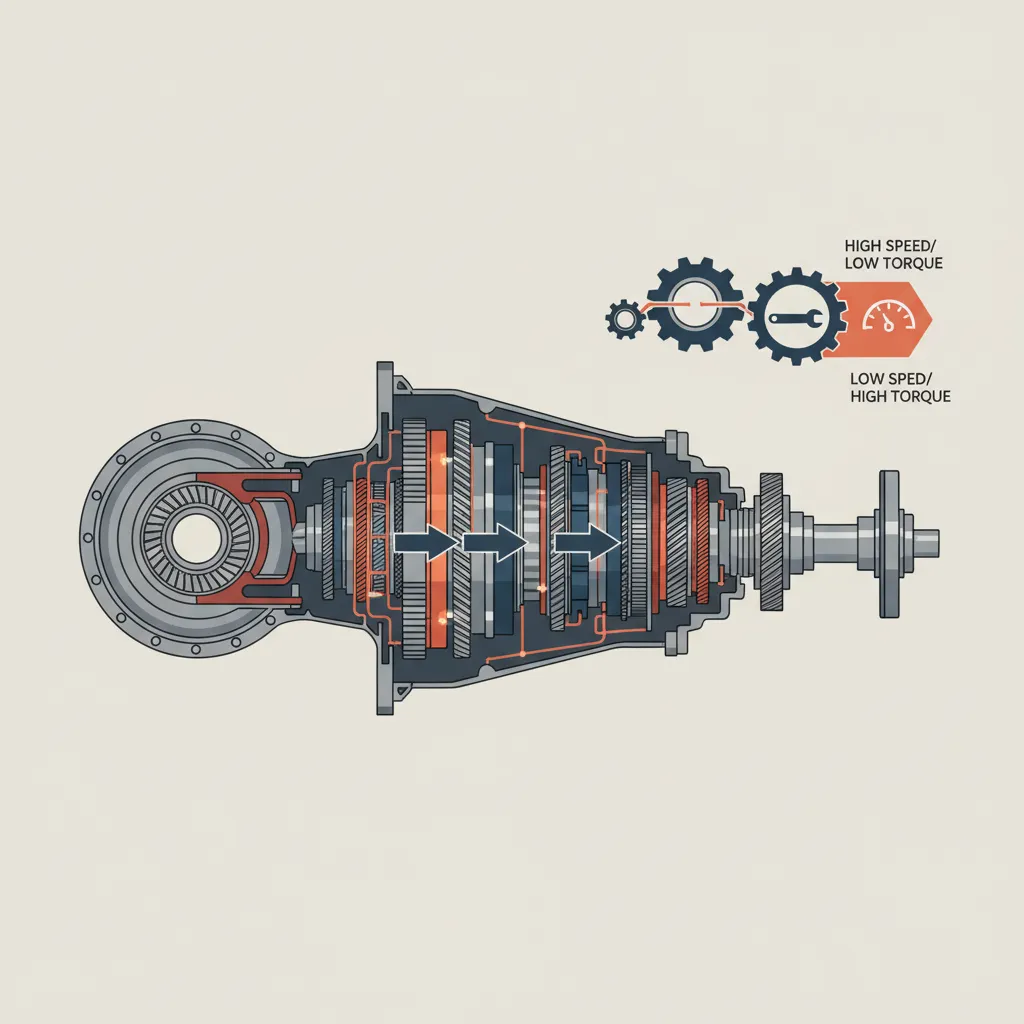

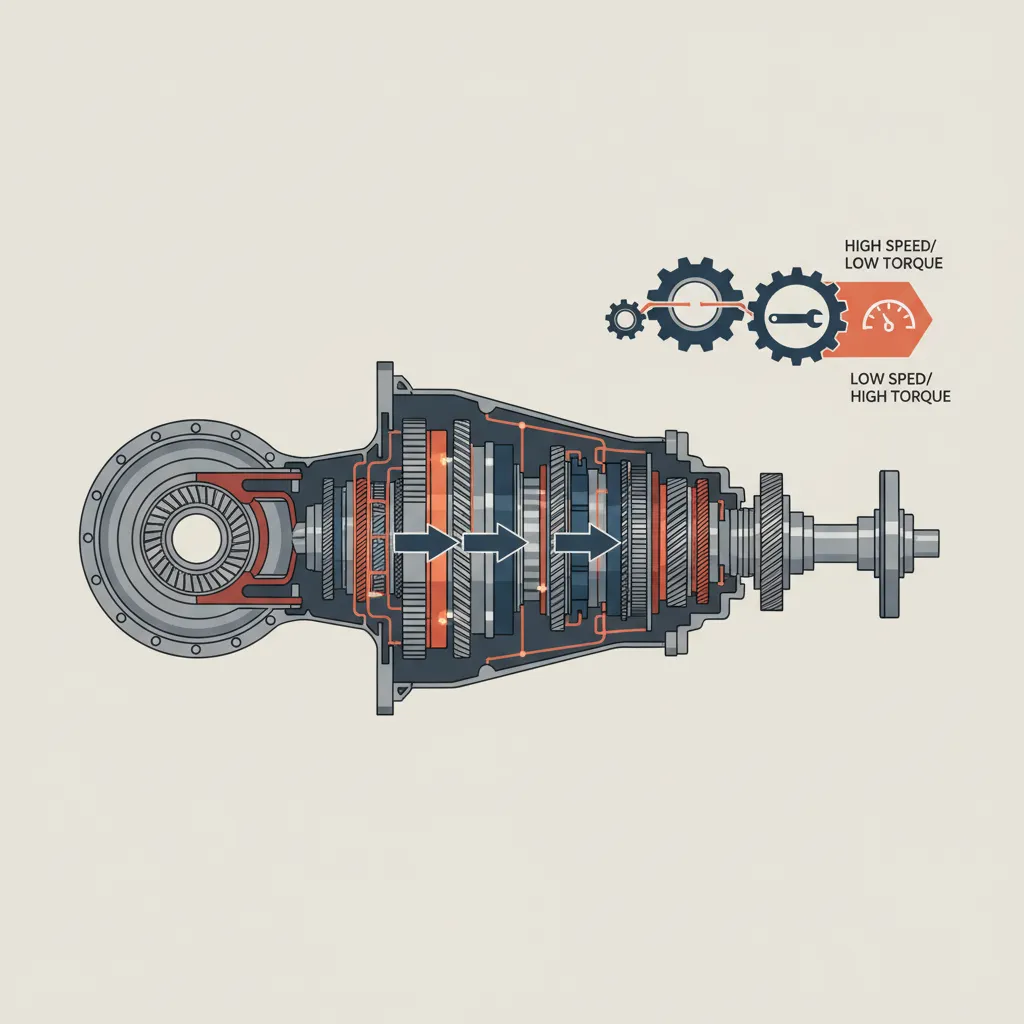

Mechanical Advantage and Gear Ratios

The transmission provides mechanical advantage through different gear sizes. Think of a multi-speed bicycle: when you encounter a steep hill, you switch to a large gear on the wheel. This requires you to pedal many times to move the wheel once, but it provides the leverage needed to climb. Conversely, on flat ground, you switch to a smaller gear to travel further with each pedal stroke.

In automotive terms, 1st gear is a “low” gear with a high ratio (e.g., 4:1), meaning the engine spins four times for every one rotation of the transmission output. This provides massive torque to overcome inertia. As the vehicle gains momentum, the transmission shifts to “higher” gears with lower ratios (e.g., 0.8:1), where the output spins faster than the engine, allowing for high-speed cruising at low engine RPM.

The Path of Energy Flow

Rotational Source

Torque Modifier

Power Transfer

Final Movement

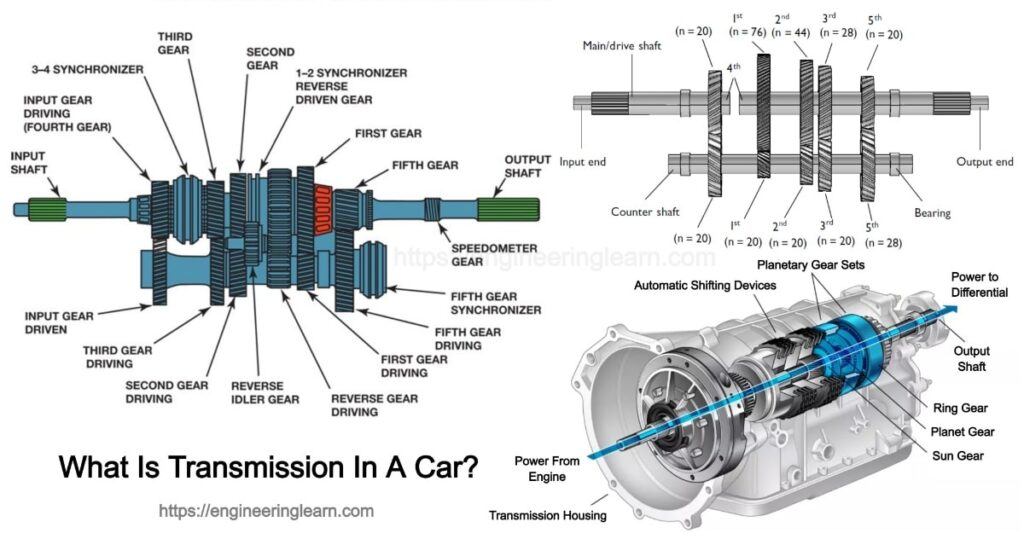

Manual Transmissions Explained: The Traditional Gearbox Architecture

The manual transmission is the purest form of automotive gear selection. It relies on a clutch assembly to act as a bridge between the engine and the gearbox. When the driver presses the clutch pedal, a pressure plate releases its grip on the friction disc, effectively disconnecting the engine’s power so the driver can select a new gear ratio without grinding the teeth of the gears.

The Internal Layout: Shafts and Synchros

Inside a manual gearbox, power flows through three primary shafts:

- Input Shaft: Connected to the engine via the clutch.

- Lay-shaft (Countershaft): Carries the various gear sets that match the input speeds.

- Output Shaft: Transfers the modified torque to the rest of the drivetrain.

Modern manual gearboxes use synchronizers (synchros). These are small brass rings that use friction to match the speed of the gear to the speed of the output shaft before the “dog teeth” engage. This is what allows for smooth, silent shifting. Without them, you would have to “double-clutch” to match engine RPM to wheel speed manually—a common requirement in vintage heavy-duty trucks.

Manual transmissions remain the benchmark for mechanical efficiency. Because they use a direct physical connection rather than fluid coupling, they typically lose only 2-4% of engine power to parasitic drag and heat. For drivers seeking maximum control and minimal energy loss, the traditional H-pattern gearbox is still a masterclass in engineering simplicity.

Understanding Automatic Transmissions and Fluid Dynamics

Unlike the mechanical engagement of a manual, a traditional automatic transmission uses hydraulics and planetary gear sets to change ratios. The most critical distinction is the torque converter. This fluid-filled component replaces the clutch, allowing the engine to continue running while the vehicle is stopped. It uses fluid shear to transfer power—which is why a car “creeps” forward when you take your foot off the brake at a red light.

The Planetary System and the “Brain”

Automatic transmissions do not slide gears along a shaft. Instead, they use a planetary gear set consisting of a central Sun Gear, surrounding Planet Gears, and an outer Ring Gear. By using hydraulic clutches to hold specific parts of this set stationary while others rotate, the transmission can achieve multiple ratios from a single gear cluster. This design is incredibly compact, allowing modern units like the Ford/GM 10R80 to pack 10 speeds into a casing not much larger than an old 4-speed unit.

📋

How an Automatic Shift Occurs

The Transmission Control Unit (TCU) monitors throttle position, engine load, and wheel speed sensors.

The TCU signals the Valve Body (the hydraulic brain) to open specific solenoids, directing pressurized ATF (Automatic Transmission Fluid).

The fluid pressure forces internal clutch packs to lock, changing which part of the planetary gear set is driven, thus altering the ratio.

CVT and Dual-Clutch (DCT) Variations

The automotive industry has recently pivoted toward two specialized types of transmissions: the Continuously Variable Transmission (CVT) and the Dual-Clutch Transmission (DCT). Each serves a diametrically opposed purpose in the market.

CVT: Infinite Efficiency

A CVT does not have gears in the traditional sense. Instead, it uses two variable-diameter pulleys connected by a high-strength steel belt. As the pulleys move closer together or further apart, the “gear ratio” changes seamlessly. This eliminates shift shock and allows the engine to stay at its most efficient RPM (its Brake Specific Fuel Consumption sweet spot) indefinitely. This can improve fuel economy by up to 10-15% over older 4-speed automatics.

DCT: Lightning-Fast Performance

The Dual-Clutch Transmission is essentially two manual gearboxes housed in one unit. One clutch handles odd gears (1, 3, 5, 7), while the other handles even gears (2, 4, 6). While you are accelerating in 2nd gear, the transmission has already pre-selected 3rd gear on the other shaft. The shift happens in milliseconds by simply swapping clutches. Porsche’s PDK system is the gold standard here, offering performance that no human can match with a manual shifter.

Essential Maintenance for Transmission Longevity

The transmission is often the most neglected component until it fails—and when it fails, the repair bills are substantial. The single most important factor in drivetrain longevity is the condition of the Transmission Fluid. In an automatic, this fluid is not just a lubricant; it is a coolant and a hydraulic pressurized medium. If the fluid breaks down due to heat, the transmission loses the ability to shift correctly.

Over 90% of automatic transmission failures are caused by overheating. Every 20-degree increase in operating temperature above the ideal 175°F can effectively halve the lifespan of the fluid and the internal friction materials. If you smell “burnt toast” when checking your dipstick, your fluid is oxidized and needs immediate replacement.

Recognizing Warning Signs

As an expert, I always tell my clients to watch for “The Three Ds”:

- Delayed Engagement: A pause of more than one second when shifting from Park to Drive.

- Discordant Noises: Whining, clunking, or humming that changes with vehicle speed.

- Drifting RPMs: The engine revs up while the car doesn’t accelerate (slipping).

Modern transmissions use internal magnets and high-efficiency filters to capture microscopic metallic shavings produced by normal gear synchronization. However, these filters eventually saturate. A standard “drain and fill” is usually safer for high-mileage vehicles than a high-pressure “flush,” which can dislodge debris and clog the sensitive valve body.

Regular Fluid Swaps

Extends the life of seals and clutch packs by removing abrasive particulates and acidic contaminants.

Cooler Maintenance

Ensuring your transmission cooler is free of debris prevents the #1 cause of catastrophic internal failure.

In summary, the transmission is vital for maintaining the engine’s power band through variable gear ratios, ensuring that whether you are crawling through traffic or cruising on the interstate, your engine remains in its ideal operating range. Different architectures like Manual, Automatic, and CVT offer various balances of driver control, comfort, and fuel efficiency. Regular maintenance of transmission fluid is the single most important factor in preventing premature drivetrain failure. Consult your vehicle’s owner’s manual for the specific transmission service intervals to ensure your drivetrain remains efficient for the long term. Understanding these basics is the first step in being a responsible and informed vehicle owner.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary difference between a transmission and an engine?

The engine generates power through combustion, creating rotational energy at the crankshaft. The transmission takes that raw energy and uses different gear ratios to control how much torque or speed is delivered to the wheels. Essentially, the engine creates the power, and the transmission decides how to use it based on driving conditions.

Why does a car need multiple gears instead of just one?

Internal combustion engines have a limited RPM range where they produce sufficient power. A single gear would either be too ‘low’ to reach high speeds or too ‘high’ to get the car moving from a stop. Multiple gears allow the engine to stay in its efficient power band regardless of whether the car is traveling at 5 mph or 70 mph.

What are the signs that a transmission is starting to fail?

Common symptoms include ‘slipping’ (where the engine revs but the car doesn’t accelerate), hesitation or ‘jerking’ during gear changes, unusual grinding noises, and a burning smell from the fluid. In automatic vehicles, you may also notice a delay when shifting from Park to Drive, often caused by failing internal seals or solenoids.

Is a CVT better than a traditional automatic transmission?

The ‘better’ option depends on priorities. CVTs are generally superior for fuel economy and smoothness because they provide an infinite range of ratios without shifting. However, traditional automatics are often preferred for towing and performance driving because they can handle higher torque loads and provide a more connected, tactile driving experience that many enthusiasts prefer.

How often should transmission fluid be changed?

Maintenance intervals vary significantly by manufacturer, typically ranging from every 30,000 to 60,000 miles for manual gearboxes and 60,000 to 100,000 miles for many automatics. However, under heavy towing or stop-and-go driving conditions, more frequent changes are recommended to prevent fluid oxidation and thermal breakdown, which are the leading causes of gear wear.